After Mali, Guinea is experiencing the return of the military to power. Are we witnessing the renewal of the African Praetorian paradigm?

Guinea in the footsteps of its neighbor, Mali

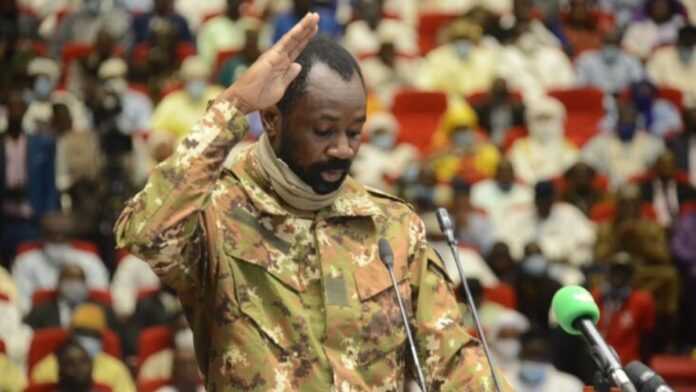

Guinean special forces officers said on Sunday, September 5, earlier in the day, that they had captured the head of state Alpha Condé and “dissolved” the country’s constitution and institutions. “We decided after taking the president, who is currently with us (…) to dissolve the Constitution in force, to dissolve the institutions; we also decided to dissolve the government and the closure of land and air borders”, said the chief of special forces, Lieutenant-Colonel Mamady Doumbouya, alongside putschists in uniform and in arms. The putschists also announced the establishment of a curfew throughout the country “until further notice” as well as the replacement of governors and prefects by soldiers in the regions.

The putsch intervenes in a context of deep post-electoral and economic political crisis (aggravated by the Covid-19 pandemic), caused by the deposed president, Alpha Condé, 83 years old, following his authoritarian abuses. Tensions escalated with the adoption in March 2020 of a new Constitution allowing him to run for a third presidential term. It will follow a violent crackdown on demonstrators hostile to his power and the arrest of dozens of opponents . Despite appeals denouncing “ballot stuffing” and irregularities, Alpha Condé was proclaimed president for a third term on November 7, 2020 and continued to lead Guinea out of challenge.

The coup in Guinea comes a year after a military junta, led by Colonel Assimi Goita, overthrew President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta (IBK) and his prime minister Boubou Cissé in Mali on August 18, 2020. There too , the putschists had declared to have ” taken [their] responsibilities ” face ” chaos ” to ” anarchy ” and the ” insecurity ” prevailing in the country by the ” lack of men in charge of his destiny “.[1] The putschists also claimed to be part of a “popular ” uprising.[2] This military interference in the political arena came after several demonstrations led by the Mouvement du 5 Juin – Rassemblement des forces patriotiques (M5-RFP), because of the war and alleged irregularities during the Malian legislative elections of 2020, repressed, have demanded the departure of IBK since early June 2020.

Like in Mali, we have seen people jubilant in favour of the military in Conakry to welcome the overthrow of President Alpha Condé.

The conclusion that can be drawn is that these two coups took place after a period of post-electoral crisis which polluted the political life of the two Sahelian countries. In addition, the peculiarity of these two coups is that the deposed presidents did not come from the barracks. Also, they seemed not to understand or master the organization and operation of the military tool of which they claimed to be the supreme commander on paper.

Praetorianism or the coup d’Etat as the most widespread mode of accession to power in Africa

This part is taken from our book ” The essential of African military political sociology ” available on Amazon [3] .

In Africa, the coup d’Etat is the most common classic form of military intervention in politics. With an often superior (if not always unmatched) capacity to exert force, the military can simultaneously defend and challenge the political authority of a government. Postcolonial history has shown that African armed forces have often tried to disregard political authority whenever it has worked against their economic, political or strategic interests. Therefore, the potential militarization of political space remains a constant in Africa.

A coup d’Etat can be defined as a sudden action – lasting from a few hours to at least a week – which often consists of the overthrow by the use of force of a government by a small group of soldiers or security forces. This results in the illegal replacement of the existing regime, the suspension or repeal of the Constitution and the dissolution of the political institutions in place.[4]

“Praetorianism” a neologism constructed from the word “praetorium” which designated the headquarters of the Roman legions and later the emperor’s guard. Political science defines it as a phenomenon of the militarization of certain elite forces, for the protection of the state. But this concept has gone astray in Africa to symbolize elite army corps responsible for protecting a given political regime, to the detriment of the defense of the national territory, with a view to the exercise and retention of power in asserting the supremacy of their strength. But Praetorianism in itself refers to military intervention in the political sphere.[5]

Starting with Egypt in 1952, Africa has seen nearly 180 coup attempts over the past six decades, over 75% of them successful. 85% of African countries have therefore experienced at least one coup attempt in recent history. But there are exceptions. Countries like Senegal or Botswana have never known one; others, like South Africa or Namibia, have known attempts but never saw a military regime take power. Indeed, there seems to be a regional “contagion” of coups d’Etat: they are much more frequent in West Africa (on average half of the African total), and practically absent in southern Africa.[6]

Although some sort of democratic consolidation has been observed since the 1990s, several instances of military interference (mainly in the form of putsch) have started to resurface across Africa’s political landscape. From military reversals in Mauritania (2008), Niger (2010) and Mali (2012), to relatively recent failures in Burkina Faso (2015), Burundi (2015), Zimbabwe (2018), Mali (2020) in Chad (April 2021) and Guinea (September 2021) – albeit to varying degrees.[7]

The main explanatory factors for the intervention of African armies in the political field

The motivations which push the military to conquer power are as manifold as they are diverse. This makes any elaboration of general causes very difficult. However, it is possible to identify some of the motivations listed during the long period of military rule in Africa. Almost all of them claim to be driven by the desire to put an end to widespread corruption or consider themselves to be mandated by society to put an end to practices blocking the functioning of political systems (DR Congo 1965, Nigeria 1966, Mali 2020, Guinea 2021, etc.); some to oppose the ideology of the civil power in place (Ghana 1966; Mali 1968) and others to promote broad social transformations.

The authors of coups d’Etat most often justify their taking action by arguments that appear legitimate but often insufficient by declaring that they want to restore democracy, constitutional order and hand over power to the people (Mobutu, General Robert Gueï in Côte d’Ivoire in 1999 while this country was sinking into an ethnic and nationalist drift around the concept of ivoirité which had become the center of all political activity since 1994, Museveni in Uganda, Laurent-Désira Kabila, Kagame, or Dadis Camara in Guinea Conakry, Assimi Goita in Mali or Mamady Doumbouya in Guinea) to try to keep it lastingly thereafter.

The confiscation and concentration of powers (executive, parliamentary, judicial) and bodies supporting democracy and the rule of law (CENI, justice, press, army, etc.) in the hands of a single person or ‘a handful of people, usually ethnically based, block any possibility of coming to power through free, transparent and democratic elections. This situation leads to a polarization of tension and popular discontent against these regimes by multiplying the possibilities of a seizure of power by force by the overthrow or elimination of the president who personifies on his own, the whole regime which is almost resting entirely on his own head (Mobutu, Habyarimana, Mamadou Tandja, Bozizé , Mugabe, Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, Alpha Condé, …).[8]

In 1960, barely 76 days after Congo’s independence, on September 14, 1960, Mobutu, then colonel and commander-in-chief of the army, established himself as the strong man of the country. In his declaration to the nation, Mobutu justifies his act in these terms: “Dear compatriots, here it is Colonel Mobutu Joseph, chief of staff of the Congolese national army, who is speaking to you about Léopoldville [today, Kinshasa, NDRL]. The Congolese national army decided to neutralize the head of state [Joseph Kasavubu, first president of the country, NDRL] until the date of December 31, 1960 […]. This is not a military coup, but rather a simple peaceful revolution. The army will help the country to solve its various problems which are becoming more and more acute”, he had launched to announce the “neutralization”of the executive.[9]

Five years later, Mobutu did it again and took power definitively on November 24, 1965 after bringing together a group of senior officers and generals called “companions of the revolution “. On the morning of November 25, the national radio broadcast military music. Then, in a short speech [10], Mobutu informs the Congolese that the national army had seized power, removed President Kasavubu from office and suspended the Constitution.

Generally speaking, coups d’état occur for reasons which will be discussed in the following points.

The coup as a corollary of the failure of state building and a response to political instability and economic underperformance

The intervention of the army in the political sphere of many African states is, for the most part, the consequence of the difficulties previously observed in the process of national construction and state consolidation. Indeed, factors such as political weaknesses and economic underperformance, corruption and the lack of institutionalized democratic structures, insecurity or the authoritarianism of power constitute arguments put forward by the military to justify their coups d’état.[11] This is the case with recent coups d’Etat in Mali and Guinea.

According to Samuel Huntington, military interference in the political sphere is more of a political problem than a military problem, and this observation remains particularly valid for most African countries.[12] In the absence of firmly established rules and strong institutions that govern the state and regulate political processes, labor unions, students, clergy, pressure groups and the military all compete for control of power of State. This is a feature of the political environment of the post-independence period in many African countries. Given their size and intrinsic influence, the African armed forces have thus become major players on the political scene and have retained this privilege.[13]

In addition, in the post-transition coups of the 1990s, we find justifications already mentioned during the first coups of the 1960s (the army, symbol and model of society’s cohesion; the army referee authorizing itself to intervene if the regime no longer satisfies the population and to punish its mistakes).

The military can see themselves as guarantors of institutions, which can represent a political bias in the post-military context: “Once the military in a particular state has lost its political virginity, then the discipline of a professional tradition of ‘acceptance of civil authority is dispelled ”.[14]

The corporatist motives at the base of the army’s interference in politics

In several African states, the putsches have been motivated by the desire of military personnel to improve, or at least maintain, their position. It is above all about the corporatist motivations which were at the base of these blows. Indeed, if other causes can be invoked, they seem to be secondary to this one.[15] The African armies coming from the better pampered and equipped colonial armies, they quickly found themselves left behind after independence, for lack of financial means to equip and maintain them.

This state of affairs quickly transformed the African armies into armies of mutineers and ” putsch armies “[16] , and thus explains the military coups. These military coups therefore have their origin in problems internal to African armies – demands of a corporate nature, which the military tries to put forward by using the resources at their disposal, that is to say force or the threat of the use of force. A distinction should be made between the purely corporate reasons in question here, and those relating to the taking over by the army of ethnic or regional interests. The demands of the military quite often relate to improving or at least maintaining their living conditions.

The motives specific to the structure and socio-political environment of the army

In Africa as everywhere, the myth of the professional military, deaf to non-military issues dear to Huntington has fizzled out. We must understand the army as an institution but also and above all as a political actor with specific interests, calculations and actions. The socio-political environment [17] of the army is as important as the characteristics and dynamics of the army: “The vast majority of sub-Saharan soldiers maintain a ‘fragmented’ (rather than integral or diffuse) relationship with their environment. Intra-military cleavages (ethnic, regional, religious, etc…) and, to a lesser but increasing extent, vertical (class) alignments with traditional horizontal cross-sectional affiliations coincide with societal divisions and make possible the creation of clientelist networks between civilian and military actors”.[18]

It is necessary to analyze the borders and the nature of the transactions between the armed forces and their societal context[19] without neglecting the internal chemistry of the institution. The army cannot be assimilated only to an element reacting to social crises.[20] It is also necessary to see how the internal mechanisms of organization and the social relations at the level of the army translate and refract the social and political crises. But above all, it is necessary to understand how “the evolution of military structures, forms of divisions and solidarity, ideological arrangements, the internal distribution of power between military layers, units and factions, etc., influence the way in which the army assimilates and reacts to crises or forges links with the forces of social tension ”.

The army is also a crisis ground. This “militarization of politics” in Africa cannot be understood without the corporatist dimension of African armies. The military institution is itself a structure of power and hegemony. It is also a structure of social mobility and political succession. It is then a question of highlighting the proper logics of the military institution in a given socio-political context and with a given history.[21]

Ideological motivations / Cold War

Some authors attribute the commission of the coups d’Etat in the first years of independence to ideological motivations. The desire to radically change the social structures of their countries by rooting out the oligarchic elites to embrace democracy and the rule of law has pushed some soldiers to intervene in political affairs. The most striking example is that of Captain Thomas Sankara, who led the coup d’état in Burkina Faso in 1983 with a clear desire to establish a just, reformed and prosperous society.

Indeed, the bipolar struggle between competing ideologies of the two “superpowers” (United States and Soviet Union) during the Cold War in the 20th century accentuated political tensions and reinforced military conflicts within the newly independent African states.[22] This remote ideological battle to increase their geopolitical, diplomatic, military and economic spheres of influence has made Africa their battleground, leading them into apocalyptic wars. This is the case, for example, of the DRC (1960 and 1965) and Angola (1975-2002).

Conclusion: after Mali and Guinea, is a new military-political trajectory emerging in Africa?

Does the return of clothed bodies to power in Africa bode a new political trajectory that will set a precedent in the coming years when we analyze the transversal socio-political evolution of several African countries (Benin, Togo, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Congo-Brazzaville, Rwanda, DRC, Uganda, Burkina Faso, CAR, etc.)?

The lack of transparent, credible and peaceful political alternation in Africa is a scourge that stirs up the disappointment of the African populations with regard to the importation of democracy to the West. Apart from a few rare cases, generally observed in English-speaking African states, alternation in power in Africa remains marginal and misguided, to the point that in some countries, only a coup remains the last resort to achieve it. It is this trend that seems to draw in the coming years the trajectory of several African countries where those in power remain allergic to the concept of democracy, even if on paper, their constitutions refer to this concept.

The military’s involvement in the political sphere, as we have described above, is often justified by the psychological conception of the army that both the military and African political actors have. In fact, in most African states, the esprit de corps inculcated in the army quickly turned into a caste spirit – therefore a political force – making this institution depositary and holder, in the name of the nation whose it derives its legitimacy from the monopoly of legitimate violence conferred on it by the State, a resource of power rather than being an institution of territorial defense.

The African soldier has a conception of his profession not in relation to the missions of ensuring external security, that is to say the defense of the territory, but considers his mission as a political function[23] as a resource of power or of legitimization of political authorities, often authoritarian.

African soldiers, just like political actors, do not consider the army as a republican institution supposed to play a major socio-political role in constituting or consolidating States in search of socio-political, institutional and security stability.

In Africa where praetorian or autocratic regimes still reign supported by the army, the soldiers, lacking sufficient training and information on the constitutional and sovereign function of the army, have developed a culture according to which political power belongs to them. They believe themselves to be fully-fledged actors of political power and do not see themselves having to play a peripheral apolitical role. In some countries, the army is becoming a key player in political transitions. Indeed, political transitions in Africa are never done against the military, it is done at best with , at least without.[23]

Thus, faced with the deterioration of the socio-political, economic and security situation in several African states, we must expect an upsurge in military interventionism in the political sphere in the coming years.

Don’t we say that “drive away the natural, it comes back at a gallop”?

Africa seems to be confronted with the biblical metaphor of the cast out demon who returns with seven others worse than him.

Jean-Jacques Wondo Omanyudu

Analyst and expert on political, military and security issues in Africa

Exclusive to AFRIDESK

References

[1] Press release of August 18, 2020 read on Malian radio and television.

[2] “Fundamental act” n ° 001 / CNSP of August 24, 2020 (PDF), published in the Official Journal of the Republic of Mali.

[3] The book is for sale on Amazon : https://www.amazon.fr/Lessentiel-sociologie-politique-militaire-africaine-ebook/dp/B07VXHQBGC .

[4] JJ Wondo, L’essentiel de la sociologie politique militaire africaine : des indépendances à nos jours, Amazon, 2019, p.401.

[5] JJ Wondo, ibid., p.50.

[6] Understanding African armies, Issue, Report Nº 27 — April 2016, p.25.

[7] Ibid., p.25.

[8] JJ Wondo, Coups d’État et militarocratie en Afrique post-indépendance – DESC, 6 avril 2015. https://afridesk.org/coups-detat-et-militarocratie-en-afrique-post-independance-jj-wondo/.

[9] Jeune Afrique, Dossier « RDC : la nostalgie Mobutu », Ce jour-là : le 24 novembre 1965, Mobutu prend le pouvoir, 17 mai 2017. https://www.jeuneafrique.com/281121/politique/rdc-y-a-50-ans-24-novembre-1965-mobutu-prenait-pouvoir/. Consulté le 21 décembre 2018.

[10] Proclamation du Haut commandement militaire des forces Armées

A L’invitation du Lieutenant général Mobutu, Commandant en Chef de l’Armée Nationale Congolaise, les autorités supérieures de l’Armée se sont réunies le 24 novembre 1965, en sa résidence. Ils ont fait un tour d’horizon de la situation politique et militaire dans le pays. Ils ont constaté que, si la situation militaire était satisfaisante, la faillite était complète dans le domaine politique. Dès l’accession du pays à l’indépendance, l’Armée Nationale Congolaise n’a jamais ménagé ses efforts désintéressés pour assurer un sort meilleur à la population.

Les dirigeants politiques, par contre, se sont cantonnés dans une lutte stérile pour accéder au pouvoir sans aucune considération pour le bien-être des citoyens de ce pays. Depuis plus d’un an, l’Armée Nationale Congolaise a lutté contre la rébellion qui, à un moment donné, a occupé près des deux tiers du territoire de la République. Alors qu’elle est presque vaincue, le Haut Commandement de l’Armée constate avec regret qu’aucun effort n’a été fait du côté des autorités politiques pour venir en aide aux populations éprouvées qui sortent maintenant en niasse de la brousse, en faisant confiance à l’Armée Nationale Congolaise. La course au pouvoir des politiciens risquant à nouveau de faire couler le sang congolais, les autorités supérieures de l’Armée réunies ce mercredi 24 novembre de 1965 autour de leur Commandant en Chef ont pris, en considération de ce qui précède, les graves décisions suivantes:

- Monsieur Joseph Kasa-Vubu est destitué de ses fonctions de Président de la République.

- Monsieur Évariste Kimba, député national, est déchargé de ses fonctions de formateur du Gouvernement.

- Le Lieutenant général Joseph Désiré Mobutu assurera les prérogatives constitutionnelles du Chef de l’État.

- Les institutions démocratiques de la République, telles qu’elles sont prévues par la Constitution du 1er août 1964, continueront à fonctionner et à siéger en exerçant leurs prérogatives. Tel est notamment le cas de la Chambre des députés, du sénat et des institutions provinciales.

- La République Démocratique du Congo proclame son adhésion à la Charte de l’Organisation des Nations Unies et de l’organisation de l’Unité africaine.

- Tous les accords conclus jusqu’ici avec les pays amis seront respectés.

- Sauf si le Parlement en décide autrement, les accords concernant l’adhésion de la République démocratique du Congo à la Charte de l’organisation commune africaine et malgache seront respectés.

- La politique internationale du Congo, pays africain, sera inspirée par les intérêts du continent africain tout entier. Dans cet ordre d’idées, la politique d’entente entre le Congo et les pays africains sera poursuivie et continue.

- Aucune ingérence dans les affaires intérieures de l’État, de quelque nature que ce soit, ne sera tolérée.

- Toutes les mesures d’interdiction qui ont frappé dernièrement certaines publications tant congolaises qu’étrangères sont levées à partir de ce jour. Le Haut Commandement de l’Armée

Nationale Congolaise invite les propriétaires des publications dont les installations ont été saccagées à se présenter au quartier général en vue d’obtenir les dédommagements des dégâts causés par certains éléments irresponsables.

- Les droits et les libertés garantis par la Constitution du 1er août 1964, tels que prévus dans ses articles 24, 25, 26, 27 et 28, seront respectés. Il en est notamment ainsi de la liberté de pensée, de conscience, de religion, d’expression, de presse, de réunion et d’association.

- L’Armée Nationale Congolaise s’étant tenue en dehors et au-dessus des activités politiques, tous les détenus politiques seront libérés. Cette décision ne s’applique pas aux membres des bandes insurrectionnelles ayant commis une atteinte à la sûreté intérieure de l’État.

- Il n’est point besoin de préciser que l’Armée Nationale Congolaise, gardienne de la sécurité des biens et des personnes, tant congolaises qu’étrangères, continuera à la garantir.

En prenant ces graves décisions, le Haut Commandement de l’Armée Nationale Congolaise espère que le Peuple congolais lui en sera reconnaissant, car son seul but est de lui assurer la paix, le calme, la tranquillité et la prospérité qui lui ont fait si cruellement défaut depuis l’accession du pays à l’indépendance.

Le Haut Commandement de l’Armée Nationale Congolaise souligne avec force que les décisions qu’il a prises n’auront pas pour conséquence une dictature militaire. Seuls l’amour de la patrie et le sens de responsabilité vis-à-vis de la nation congolaise ont guidé le haut commandement à prendre ces mesures. Il en témoigne devant l’Histoire, l’Afrique et le Monde.

Le Haut Commandement de l’Armée Nationale Congolaise demande à tous les Congolais de lui faire confiance. Il demande également que le fonctionnement régulier des institutions, de l’administration et de l’économie du pays soit assuré par la présence de tous sur le lieu de leur travail.

Le lieutenant général Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, assumant les prérogatives de Président de la République, prend les décisions suivantes :

- Le colonel Léonard Mulamba assumera les fonctions de Premier ministre;

- Le Colonel Léonard Mulamba est chargé de former un gouvernement représentatif d’union nationale dont fera partie au moins un membre de chacune des vingt et une provinces de la République Démocratique du Congo et de la ville de Léopoldville;

- Pendant toute la durée durant laquelle le lieutenant général Mobutu exercera les prérogatives de Président de la république, le Général Major Louis Bobozo remplira les fonctions de commandant en chef de l’Armée nationale Congolaise.

Fait à Léopoldville, le 24 novembre 1965.

Haut commandement de l’ANC

Signé :

Lieutenant général, J.D.Mobutu

Général-major, L. Bobozo

Colonels :

- Masiala, L. Mulamba, D. Nzoigba, F. Itambo, A. Bangala.

Lieutenants-colonels :

- Ingila, J. Tshiatshi, A. Monyango, A. Singa, L. Basuki, F. Malila, A. Tukuzu.

[11] Habiba Ben Barka and Mthuli Ncube, “Political Fragility in Africa: Are Military Coups d’Etat a Never-Ending Phenomenon?” African Development Bank (September 2012), 3. On February 18, 2010, Mamadou Tanja, the democratically elected president of Niger, was overthrown in a military coup. It was a reaction to the President’s decision to extend his second five-year term for three years. To cite another example: on August 6, 2008, Mauritania’s first freely elected president, Sidi Mohamed Ould Cheikh Abdallahi, was overthrown by a group of senior officers who said their action was in response to the deterioration of the social, economic and security situation in the country.

[12] Samuel P. Huntington, Political Order in Changing Societies, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1968.

[13] Emile Ouédraogo, Pour la professionnalisation des forces de sécurité en Afrique, Centre d’Etudes stratégiques (CESA), N°6, Washington, DC, juillet 2014, p.14.

[14] Céline Thiriot, La place des militaires dans les régimes post-transition d’Afrique subsaharienne : la difficile resectorisation, Revue internationale de politique comparée, 2008/1 – Volume 15, De Boeck Université. p.30.

[15] Dimitri-Georges Lavroff, Régimes militaires et développement politique en Afrique noire, Persée, Revue française de science politique, XXII (5), Octobre 1972, p.981.

[16] P.L. Van Den Berghe, « The role of the army in contemporary Africa », Africa Report 13 (3), mars 1965, pp.13-15.

[17] R. Luckhamar. “The National and International Context of Military Participation in African Politics”, Table ronde FNSP CERI sur Les processus politiques dans les partis militaires : clivages et consensus au sein des forces armées, Paris, 28, FNSP CERI, 1979.

[18] E. Hutchful, Les militaires et le militarisme en Afrique : Projet de Recherche, Dakar, CODESRIA, Document de travail n°3, 1989, p. 7-8.

[19] R. Luckhamar, “A Comparative Typology of Civil-Military Relations”, Government and Opposition, 6 (1), Hiver, 1971, p. 5-35.

[20] Céline Thiriot, op. cit., p.18.

[21] Céline Thiriot, Céline Thiriot, op. cit., p.18.

[22] Habiba Ben Barka and Mthuli Ncube, op. cit. p.7.

[23] African soldiers, like political actors, do not consider the army as a republican institution supposed to play a major socio-political role in constituting or consolidating States in search of socio-political, institutional and security stability.