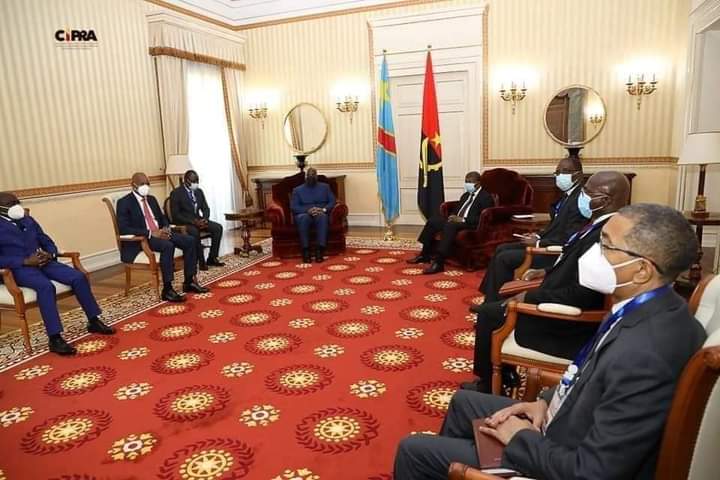

The President of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Félix Tshisekedi, went to Luanda on Monday, October 16, 2020 for a short working visit with his Angolan counterpart João Lourenço.

Tshisekedi visits Angola seeking diplomatic and military support against Kabila

Speaking to the press after the meeting, Tshisekedi revealed that he had come to Luanda to share with the Angolan head of state the ideas he is currently developing as a way out of the political crisis in his country. He also said that he took advantage of the mission to discuss aspects related to bilateral cooperation with President João Lourenço, with particular emphasis on the exploitation of hydrocarbons. The Congolese president said he had asked Angola, in addition to its diplomatic and political support, to help build the capacity of its defense and security forces. “I came to see my counterpart, President João Lourenço, to inform him of the situation that currently exists in my country, of my plan to end the crisis currently reigning in the DRC”, said Tshisekedi. He said that he left Angola “very happy, very satisfied “, because the explanation and the proposals he gave were accepted by his counterpart.” First of all, diplomatic and political support, but also support for strengthening the capabilities of our defense and security forces, ”he said.

An Angolan diplomatic source also confirmed to us that Félix Tshisekedi went to seek diplomatic support from Angola in the face of the political crisis in the DRC. Since assuming power in January 2019, President Félix Tshisekedi has maintained excellent diplomatic relations with his Angolan counterpart João Lourenço. It was in Angola that the Congolese president made his first state visit abroad after his inauguration. Since then, the two presidents have met regularly around issues related to economic, diplomatic and security issues in the region and between the two countries.

Angola, the kingmaker in the DRC since 1997

It should be noted that Angola played a decisive role within SADC, alongside South Africa, in forcing Joseph Kabila not to stand for a third term. Angola shares more than 2,511 kilometers of common land border with the DRC. The two countries also share a common maritime area which is often the subject of dissension between the two countries in the context of oil disputes at sea located opposite their coasts, in the Atlantic. This is a dispute that has been the subject of UN arbitration since 2010. According to Kinshasa, Angola exploits many deposits facing its coasts and the enclave of Cabinda (north of the river Congo). Kinshasa considers that most of the oil production off Cabinda actually belongs to DRC. It is a maritime zone which abounds in important offshore reserves in the zone of common interests (ZIC) created by the former presidents José Eduardo Dos Santos and Joseph Kabila in July 2007 in Luanda.

Border relations between the two countries have not always been cordial. The Congolese government has regularly denounced Angolan military incursions into its territory, often claiming to be in pursuit of elements of the Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda (FLEC). As a reminder, between 2007 and 2012, Angolan troops had occupied Congolese villages in the province of Bas-Congo to counter the presumed presence of the FLEC, causing population displacement. In August 2011 and in May and November 2012, new fighting broke out in the Tshela region (DRC) between the Angolan Armed Forces (FAA) and FLEC combatants. Likewise, in January 2007, Angolan troops had already occupied thirteen Congolese localities in the territory of Kahemba and its surroundings, in the province of Bandundu. The Angolan flag had been hoisted there, against a background of contestation of the border line. The territory of Kahemba has rivers whose alluvium is particularly rich in diamonds. Since 2003, several thousand Congolese illegal diamond diggers have been expelled from the neighboring Angolan provinces of Lunda Norte and Sul. The lack of reaction from the Congolese authorities, to the sending of several confidential reports, by Angola, relating to the activities of the FLEC on Congolese territory, could shed light on this movement of mood on the Angolan side and the territorial incursion of October 2013.[1] Since 2017, following the deadly conflicts in Kasai, the Angolan army has deployed its military infantry, supported by tanks and heavy artillery, along the common borders of the west and north-east of Angola, in the provinces of Lunda Norte and Mexico, which hosted the bulk of Congolese refugees. On the other hand, Kabila had taken care to deploy anti-aircraft batteries and troops loyal to him along the Angolan borders to face any attempted Angolan military incursions into the DRC.[2] These units still remain active to this day.

Angola has also played a very decisive military role in the major political changes that have taken place in the DRC since 1997. Its decisive intervention in Kenge (ex-Bandundu) in April-May 1997 against elements of Mobutu’s DSP and UNITA rebels from Savimbi broke the military lock that allowed AFDL troops to move up to Kinshasa. In August 1998, it was the Angolan troops, who came in extremis to the rescue of Laurent-Désiré Kabila, who routed the rebels of RCD-Goma and special units of the Congolese army in Bas-Congo. In March 2007, it was again the Angolan army which provided decisive support to Joseph Kabila, whose GSSP (Special Presidential Security Group) was in difficulty by elements of Jean-Pierre Bemba’s DDP.

Angola, an absolute military power in Central Africa

The Angolan Armed Forces (FAA) currently stands at 107,000 soldiers, including 100,000 for the land force, 6,000 for the air force and 1,000 for the navy. To these numbers must be added 10,000 men from the paramilitary force in charge of presidential protection and 10,000 rapid reaction police officers responsible for internal security. The FAA have around 300 tanks and a hundred fighter planes. The Angolan army has the advantage of being well trained and having good counter-insurgency capabilities as well as powerful combat aviation and transport capabilities unparalleled in Central Africa.[3]

Angola, because of its geostrategic ambitions, is developing a hybrid military strategy, aimed both at securing its internal territorial space by asserting its sovereignty over its national space to avoid relapsing into civil war, of its natural resources, as well as the propensity to exercise de facto regional “tutelage” over its neighbors.

Angola is one of the models of African countries which has been able to successfully reform its security services (SSR) in times of war or in a fragile post-conflict situation by putting in place an effective and efficient defense system. Between 1990 and 2002, Angola developed the military doctrine of ” combat performance [4] ”by engaging in the modernization and equipment of its army. This ambitious military tool modernization program has placed particular emphasis on improving and strengthening the firepower of the FAA air component [5] , with the acquisition of a significant number of Russian military planes of all kinds and the deployment of an anti-aircraft defense system (DCA), which played a decisive role in crushing the rebellion of UNITA or in the intervention of the Angolan army in Sao Tome, Congo-Brazzaville, DRC and other areas of military operations, in particular by leading offensives towards the south of the country. [6]

Indeed, because of its experience of a long civil war, and its conception of national security, Angola has favored since the second half of the 1990s, its own solutions (military or negotiated) to regional security issues often favoring a “statist”, bilateral approach (relations with the two Congos) to multilateral regional approaches.[7] Until 2002, the priority for the Angolan government was then exclusively ” the defense of the nation “, by pacifying and securing the country’s borders. However, due to the international and cross-border nature of the Angolan conflict, the FAA also, from the second half of the 1990s, applied the doctrine of ” forward defense”[8] ”by going to intercept threats beyond national borders, in a non-hegemonic vision at first, in the DRC and Congo-Brazzaville.

At the start of the 2000s, Angola seemed to be making a shift in its military strategy towards an expansionist security approach. Indeed, beyond the initial security concerns – linked to the situation of instability that prevailed in the two Congos at the end of the 1990s – the subsequent military interventions of the Angolan army in these two countries also seem to respond to geoeconomic motivations. The presence of oil resources in the border areas between Angola and the DRC, for example, could explain the recurrence of tensions, because the delineation of the borders is a source of controversy.[9] But in recent years, Angola has initiated a new strategic dynamic in its doctrine of employment of its armed forces. Angola shows an apparent desire to become a major player in the regulation of international relations, in particular through its active participation in the resolution of regional crises and issues related to peace and security in southern Africa – within SADC – , in Central Africa – ECCAS – as well as in the Gulf of Guinea.[10]

Angola, the strategic actor by proxy of the United States and the EU in the Congolese crisis

Inescapable regional military power and tested several times in crises in the DRC, no Congolese political actor can do without Angolan military support in the event of an internal political crisis. This is what President Tshisekedi has unofficially requested to try to counter the military influence of Joseph Kabila on the army in the event of a violent rupture of the ruling coalition in the DRC. According to several Congolese military and diplomatic sources in Kinshasa, President Félix Tshisekedi would have escaped an attack last week, carried out by military elements not otherwise identified.

It comes to us exclusively from an Angolan security expert source that Tshisekedi returns from Angola with a firm promise to be supported by Angola : ” the important information is that there will be military ‘support’ / Angolan security in DRC to support Tshisekedi. I don’t know what genre yet, but Lourenço gave him his agreement in principle ”. It must be said that since the defeat of Savimbi, Angola has maintained excellent military relations with the United States of America. These relations have been strengthened since the accession of Lourenço to power in 2017. The latter also maintains very close relations with the European Union with which he worked together in the Congolese pre-electoral crisis in order to force Kabila to leave power.

If Tshisekedi seems to obtain in Angola, agent of the West, significant diplomatic support against Kabila, real politik obliges, his closing speech for the popular consultations he initiated will be decisive in indicating the direction he intends to give of his standoff with Kabila. In view of the evolution of the very tense political climate in the DRC, a rupture of the ruling coalition would more than almost inevitably lead to a shift in the political crisis towards a military confrontation between the two camps that glare at each other from the start of the facade alternation following the 2018 botched elections. In this case, only the active forces present on the ground will determine the outcome of the issue in a country where Kabila does not seem ready to effectively withdraw from the power he is trying to control through the strategy of “leading from behind. ” Faced with other indecisive internal and regional external military players, will Angola be enough to make the difference on its own as in the past? We hold our breath because we are told of a strong tension that smolders within the dressed bodies …

Jean-Jacques Wondo Omanyundu

Expert in security issues in the DRC and Middle Africa

Notes

[1] LUNTUMBUE & WONDO, « La posture régionale de l’Angola : entre politique d’influence et affirmation de puissance », GRIP, Bruxelles, 3 juin 2015.

[2] JJ Wondo, Les cinq principales dimensions de la crise congolaise : enjeux et perspective – 10 juillet 2018. https://congokin.media/2018/07/10/les-cinq-principales-dimensions-de-la-crise-congolaise-enjeux-et-perspective-jj-wondo/.

[3] Laurent Touchard, Les Forces armées africaines 2016-2017. Organisation, équipements, états des lieux et capacités, Editions LT, 2017, p.323.

[4] The English concept of “Combat performance” refers to the program undertaken by the Angolan army in the 1980s and focused on the substantial improvement of military capacity and performance through the acquisition of significant equipment worthy of a conventional army. Headquarters, Department of Army, Angola – a country study, Washington, 1991, pp. 203-257.http://www.marines.mil/news/publications/Documents/Angola%20Study_5.pdf.

[5] Michel Luntumbue et Jean-Jacques Wondo, La posture régionale de l’Angola : entre politique d’influence et affirmation de puissance, Note d’analyse, GRIP, 03 Juin 2015.

[6] Jean-Jacques Wondo Omanyundu, L’essentiel de la sociologie politique militaire africaine, Amazon, 2019, p.181. Disponible sur Amazon : https://www.amazon.fr/Lessentiel-sociologie-politique-militaire-africaine/dp/1080881778.

[7] Eugénio Costa Almeida, Instrumentality Power: or Angola, a Regional Power in Crisis Growth, Academia, mai 2014.

[8] J. Nye définit le Forward Defense (défense de l’avant) comme étant la capacité pour un pays d’aller intercepter les menaces le plus en amont possible de leur réalisation, au-delà de ses frontières. Annuaire Stratégique 2003, p.282.

[9] LUNTUMBUE & WONDO, « La posture régionale de l’Angola : entre politique d’influence et affirmation de puissance », GRIP, Bruxelles, 3 juin 2015.

[10] Van-Dúnem, A política externa angolana na agenda nacional de consenso, Politica e diplomacia intra-africana em dabte, 24 avril 2009.

One Comment “Angola in military rescue of Tshisekedi in his standoff with Kabila ? – JJ Wondo”

Wizdom

says:Great